Why it matters and what regulators are doing to address it

In the production of this annual Compendium, we strive to curate and present information without imposing our own views of such—except in those sections cleverly entitled, Our View. This year’s report has three such segments, contributed by our esteemed advisors.

Our thanks go to:

Despite best efforts to be neutral observers and reporters, bias will inevitably intrude in any such reporting exercise, if only in the choices we make about what to include and exclude from this report. We seek to mitigate that bias by inviting input from those whose opinions we seek to convey, and this we do in two ways:

We were delighted to receive comprehensive survey responses and other commentary from the UK Financial Conduct Authority, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the European Banking Authority, and the Dubai Financial Services Authority, among others. Their contributions are captured throughout this report, greatly enriching it. We are grateful to them for taking the time to share their thoughts and perspectives. Particular thanks go to:

Lastly, our special thanks go to those who took the added time to provide us with detailed remarks appearing in this year’s In Focus segments:

We hope that this 2020 update to our annual Compendium will help to prompt further informed discussion among banking industry executives and their regulators regarding: the role that culture plays in driving misconduct risk; how such risks are to be better managed, supervised, and mitigated; how we might come to benefit by leading indicators of such risks through the use of data technologies; and how employee conduct may be managed proactively to drive desired performance outcomes.

As always, we welcome any questions, comments, or criticisms, along with suggestions as to how we may improve next year’s report. Please reach us at info@starlingtrust.com.

In Focus:

The Future of Operational Risk Management

by Mark Cooke & Simon Wills

Current approaches to the management of operational risk need to evolve rapidly to be effective in today’s digital environment. Also referred to as nonfinancial risk, these fall outside the standard set of financial risks (credit, market and liquidity, etc.). Rather, the operational risk portfolio includes things like cybercrime, outsourcing, data security, AI use, and the risk of employee misconduct and poor company culture.

The current standard approach to managing such non-financial risks relies overmuch on 'systems of record' and administrative processes that seek to categorize risks, register their controls, assess those controls on a periodic basis, and then create inventories of the issues that appeared and actions that were taken. This approach has a high cost and is not delivering the required outcomes.

At ORX we believe that the digital businesses of tomorrow will require a far more dynamic and embedded approach, one that works proactively to prevent failure as part of ongoing operations, and not as some bolted on after-thought. That embedded approach requires a focus on fostering the right behaviours, combined with exploiting newly available unstructured data sets and making smart use of latest generation technological tools.

The financial industry is undergoing considerable change driven by technological disruption. As a consequence, so is risk management across our industry. The risks we face are evolving quickly and we will need different techniques and methods to manage them effectively going forward. At ORX, we have been working with our members to support them through this time of transition, by providing a platform across which we can act collectively to identify emerging challenges, share evolving best practices, and create standards that can help the industry to better manage the risks we face together.

ORX is a not-for-profit financial industry association that works with its members to build a safer global financial system, promoting sound nonfinancial risk management practices, while providing a platform to share risk and loss data. The association has developed standards that enable the sharing of such data and insights—something that is only possible and meaningful through cross-industry collaboration. Such collaborations are at the core of other industries, such as aviation, where data is shared between airlines to ensure that highest levels of safety are maintained by all.

The overarching aim at ORX is to promote, within the financial industry, practices and behaviours that address past failures—which have done so much harm to public trust in the financial system—and to get ahead of newly emergent risks. Over the recent past months, we have been working with industry Simon Wills, ORX Executive Director Mark Cooke, ORX Chairman 39 participants on two specific agendas that relate to the future of risk management: first, the promotion of a common risk taxonomy across the financial services industry; and, second, we are looking at how digital disruption will require the industry to reshape its risk management practices going forward.

Taxonomies don’t sound exciting, but they should be recognised as essential. They are the means by which we describe problems, the basis from which we collect and categorise data, and the manner in which we then conduct analysis and collate learnings. Try and describe the natural world without a taxonomy and you’ll quickly run into trouble. The current taxonomy for operational risk was invented before the iPhone and, although it has stood up surprisingly well, it has started to show its age. A taxonomy that doesn’t contain information security risk, model or thirdparty risk, etc., simply isn’t fit for the present, let alone the future.

The new ORX Reference Taxonomy is based on the actual taxonomy used among approximately 60 ORX members. The result reflects a combination of machine learning and human judgement. We describe operational risks by what risk events took place and, this year, we are working to agree on how we best describe the impacts and the causes of such risk events. (As a service to the industry, our work is published on the ORX website.)

Risk managers should become behavioural engineers.

Our work on taxonomy is emblematic of the changes we see in the operational risk profile across our industry—changes that will drive new ways of managing risk. One example, addressed by our new taxonomy, is the focus on specific material risks such as cyber. Peer-sharing of related risk information, data, practices, expertise and experience regarding cyber risks will enhance the development of effective and efficient risk management, and ORX is leading the way with its Cyber Service, launching during 2020.

Like our business colleagues, we are focused on the potential to access and analyse new data, to automate previously low value manual tasks, and to embed robust nonfinancial risk management into the day-to-day processes of our businesses. These are the low hanging fruits of digitalisation that make most sense to our current generation of managers.

However, the digital playbook presents other less obvious opportunities. What is the potential for shared platforms in the risk space? How can we help to develop a vetted ecosystem of regtech applications and suppliers? If we go this route, then what compromises might we need to accept in terms of standardisation of data and functionality? Might risk management need to become more 'commoditised' in the main so as to free up resources to apply to really unique problems and opportunities? The industry needs to wrestle with these questions collectively, now, if we are to capture the fullest opportunity for improvement.

Banking has had a difficult decade. After the Financial Crisis, the industry suffered a long tail of losses associated with conduct and culture. Over the last few years, we’ve started to escape from our past and we now need to look to the future. Perhaps the biggest opportunity here lies not in the application of computer science but behavioural science.

The risk function exists to inform and bound better decision-making. Behavioural science is, at its core, the science of making better decisions about human behaviour. Currently, it is applied most often to efforts aimed at influencing the decisions of consumers and others external to the firm. The future should be about how to positively influence the behaviour within our organisations and among our managers and employees. If we aim to restore trust in our industry, nonfinancial risk managers must become behavioural engineers.

Mark Cooke, is former Group Head of Operational Risk at HSBC and former Chairman of ORX, now serving on the Risk & Governance Advisory Board at Starling.

Simon Wills, ORX Executive Director

In Focus:

Further On up the Road

by Gary Cohn, Tom Curry & Martin Wheatley

Those old enough to recall the collapse of the Soviet Union will remember how time seemed to accelerate, as established truths toppled like dominoes. Addressing Congress in February 1990,1 Václav Havel captured the moment: “The human face of the world is changing so rapidly that none of the familiar political speedometers are adequate,” he said, describing a breathless disorientation when he added, “we have literally no time even to be astonished.”

History sometimes lurches away from the deeply familiar into an ill-formed “new normal.” But it also has a way of lingering, leaving elements of Whathad-Been deeply interred—in the earth and the national psyche—to be rediscovered in the course of the Yet-to-Come.

Consider the 1940 image above, warning of an unexploded German bomb found lying beneath London’s Fleet Street. Then consider this story2 of WWII-era bombs found in Dortmund—reported on January 12th of this year. Or this story,3from February 2nd, when another bomb was found in Venice. Or this one,4appearing just a day later, when yet another bomb was found under Dean Street in London’s Soho. History lurches, true, yet it also lingers…

We are again living through a time of lurching, when “political speedometers” are insufficiently well calibrated to the pace of change.

In the face of the current pandemic, and the economic dislocation it has occasioned, we must throw as much money as possible, as quickly as possible, at floundering businesses, entrepreneurs and sole proprietorships, gig economy workers and households in order to create conditions for a swift recovery. To do so, we will be forced to rely on the banking sector to play its critical intermediary role5 as perhaps never before.

In support, bank regulators worldwide are putting a hold on the introduction of new regulations and delaying normal supervisory and oversight activities: the Basel Committee has pushed the deadline for implementing Basel III standards out by a year; the US Federal Reserve Bank is working to ease rules;6 the UK’s Prudential Regulatory Authority has cancelled its 2020 stress tests;7 the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has suspended much of its regulatory work through September8 and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission has suspended its “close and continuous monitoring” program.

In Asia, banks and regulators have benefitted by their experience confronting SARS in the early 2000s, and they have had longer to adjust to the pandemic. Today, banks across the region appear to be in a competition of sorts, aiming to burnish their credentials and social standing.

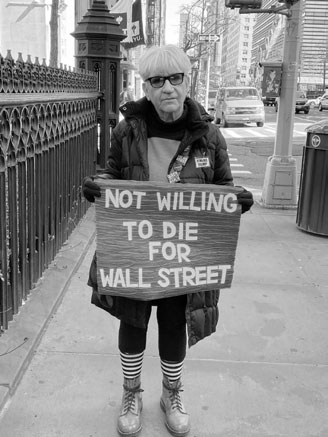

Others must follow their example. Over a decade after the Financial Crisis, Banco Santander chair Ana Botín reminds, bankers remain distrusted9 around the world, contributing to current political populism. The 2008 Financial Crisis originated in the banking sector—it was the banks that needed saving. But the subsequent “bailouts” bred a lingering resentment,10 and many still feel that banks first caused the crisis and then benefited at the taxpayer’s expense.

Today’s trials reverse that dynamic: the current pandemic positions banks to reciprocate and to extend themselves on behalf of the taxpayers. But optimism here is unfortunately wanting.

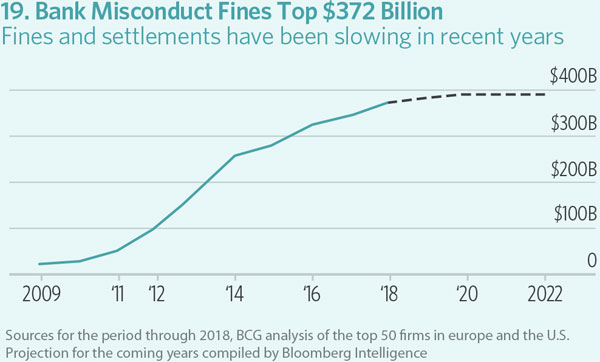

The years since the Financial Crisis have witnessed countless misconduct scandals, among banks in every major market across the globe. Despite enormous investment in governance, risk and compliance systems, processes and personnel, efforts to manage culture and conduct related risks in the financial sector in the last decade have proven demonstrably inadequate. Throwing more resources at past failed approaches is senseless—perhaps even irresponsible.

Once our present crisis is past, we fear that we will learn of yet more industrywide misconduct, this time taking place as trillions of dollars were steered through the global banking system in order to support taxpayers. Assuredly, some firms will seize upon our current circumstances as a much-needed “redemption moment”11 for the industry. But this will not insulate good actors from the inevitable social blowback that will result from the bad acts of even a relative few.

“What struck me when the manipulation was made public was how much it angered people,” one of us observed12 a few years after the Financial Crisis, when the LIBOR rate-rigging scandal broke into public 118 Culture & Conduct Risk in the Banking Sector view. “It said something about the culture of financial services, but also led people to question what they can rely on.”

In this time of lurching, we must pause to consider what may linger well into the future.

Though supervisory scrutiny by regulators may be suspended, rather than viewing this as a “compliance holiday” of sorts, we believe that a doubling down on nonfinancial risk management should be an industry-wide priority. We cannot afford to allow a public health and economic crisis to become a moral crisis as well.

History lingers. “If this epidemic results in greater disunity and mistrust among humans,” warns Yuval Noah Harari,13 “it will be the virus’s greatest victory.”

If we fail to address the financial sector’s Achilles' Heel14- misconduct risk—in the course of what Mohamed El-Erian has termed a race between economics and COVID-19,15 a spate of scandals will almost inevitably follow our current heroic efforts. This will rob the financial industry of what little public trust16remains to it, likely deepening an already worryingly broad discontent with capitalism—and perhaps even with democracy itself.

Policymakers, regulators, supervisors, boards and bank leadership and risk officers should consider this closely if they wish to avoid a future crisis, as pandemic-era bombs explode further on up the road.

A version of this article was published by Thomson Reuters Regulator Intelligence on April 1st, 2020 and again, on April 13th, Here.17